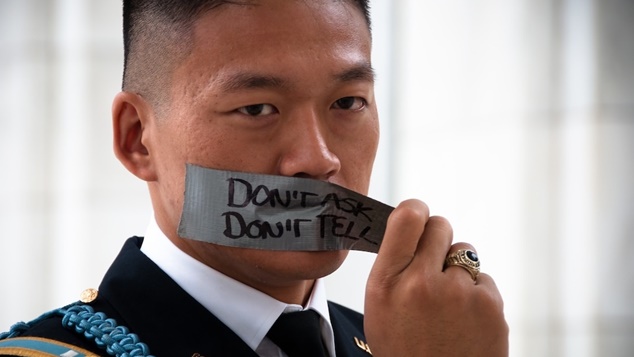

In October 2009, former US infantry lieutenant Dan Choi took to a stage at George Washington University and said nothing. In true military fashion, he remained statuesque while his mouth was sealed with a strip of silver duct tape and the words ‘Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’ scribbled in permanent marker.

The face of this Korean-American soldier has become synonymous with the United States’ notorious DADT legislation for the past couple of years. The Iraq veteran and Arabic linguist practically fell into activism after he came out on national prime-time television news and was then shortly discharged from the defence forces. From that point on, the lieutenant would no longer battle for the US military but against it.

Under DADT, the US military has fired an estimated 14,000 defence personnel due to DADT since 1993, that’s more than enough people to fill the Burswood Dome or roughly about two people fired each day since 1993.

US President Bill Clinton introduced the policy in 1993 as a compromise to allow homosexual servicemen and women serve in the military, it limited the military’s ability to ask members about their sexuality (don’t ask) as long as homosexual members didn’t reveal it (don’t tell).

Next month on September 20, the US Congress will remove the controversial DADT legislation from US law, finally allowing openly gay US defence personnel to come out and not be fired. The discharged lieutenant spoke to OUTinPerth from New York City this month about his fight to fight for his country.

Born in 1981, Dan Choi struggles to recall when he first decided he wanted to become a soldier. “Maybe when I was a sperm,” he laughs.

“The thing that sealed the deal for me was that film Saving Private Ryan, the Stephen Spielberg film with Tom Hanks back in ’98.”

Choi had just come out to his family and after watching Spielberg’s blockbuster, he found a brochure to West Point Military Academy that his brother had left lying around. From 1999 to 2003, Choi trained in one of the world’s premier leader development institutions. He graduated, ready for war in Iraq.

“I was very different then to what I am now.”

“I found myself very excited as a young man needed in society,’ he said, “bridging that gap, not only as an Arabic linguist but as an Asian face in a war where white or black soldiers are the typified American monster and to see something out of the ordinary, changes the dynamic of the entire military operation.”

As a lieutenant and team leader, Choi served in a combat unit for the US infantry. He had served under the DADT law for 10 years with aspirations to be the first Korean-American General.

“I knew that I was gay before I went but of course I thought it was a phase, I thought it was a sin, I thought I could ignore it.”

By March 2009, Choi had had a change of heart and published his coming out in a media release as the spokesperson for Knights Out – a LGBT network of West Point alumni. Naïve to the workings of the media, he called on everyone available to him via email.

“I didn’t have any media experience; I just sent the press release to everyone who had ever emailed me for the past of years, I got a lot of pushback for that, a lot of hate mail.”

The blogosphere picked up on Choi’s announcement and before he knew it, the Wall Street Journal and Army Times had reported on it. Then on national television, he told America he was a soldier of the US infantry and he was gay. Choi said Knights Out was never meant for activism but a reference point for West Point officials to better understand gay and lesbian recruits.

“I had no idea I was going to be an activist.”

“It had transformed into real activism because of two major things: as our profile increased, we increased our numbers by 23 in the beginning to 40 by that weekend and now there are 500.”

“And there’s quite an impetus to keep doing it when soldiers reach out to you and say that they were suicidal, that’s when you have to keep being an activist.”

Choi did not have wait too long before he reaped the consequences. Choi swiftly received his letter of discharge for ‘moral and professional dereliction’ of duty. Two options were afforded to Choi, in order to stay in the forces, he could pretend he never went on national television or at least release a retraction and apologise; the second choice was to challenge it in front of a tribunal.

‘I knew it was going to happen so I don’t claim victimhood; I just know [the] emotions are just as visceral, they’re just as painful even if you expect it to happen.’

‘I just decided on my own that I was going to challenge this.’

By mid 2009, he had rejected the offer of clemency and decided to fight the charge. Despite his appeal to a panel of New York National Guard officers and a petition of more than 160,000 signatures supporting Choi, the lieutenant was discharged from service on 30 June, 2009.

“When I got kicked out finally, it took a year for them to discharge [me].”

‘They ended up giving an honourable discharge so none of the benefits were immediately cut off, it was only since December [2010] that they’ve tried to cut off my veteran’s benefits.”

In 2010, he was arrested twice for handcuffing himself to the White House fence and spent seven days on a hunger strike for an end to DADT.

“The most bewildering thing about getting kicked out of the military for most people, particularly when they get kicked out for being gay is they feel they don’t have purpose anymore and immediately want to go back even though the military had done such harm to them.”

In October 2010, Pentagon officials began instructing military recruiters to start enlisting openly gay and lesbian people. The announcement came a year after the iconoclast had stood upon the stage with his mouth taped shut. The move was a reaction to a Federal Court decision that ruled that Don’t’ Ask Don’t Tell as ‘unconstitutional’.

Choi, like many others would try to re-enlist. Yet he insisted the experience was hindered by residual feelings of his discharge. “You can pull out the nail but the hole is still there,” he said.

“That was the feeling after trying to re-enlist, that there are certain experiences like war that are indelible.”

Following the Federal Court ruling, the Senate and the House of Congress voted for the DADT repeal last December. Just days before Christmas, President Obama finally acted upon his 2008 election promise of allowing openly gay and lesbian soldiers to serve. The law did not start automatically, in order to prepare about two million soldiers, however, the law will finally come into effect this month.

Reflecting on the journey that had consumed the past years of his life, Choi found some striking similarities between soldier and activist.

“I have always felt being an activist has made me a better soldier and being a soldier has clearly made me a better activist.”

“As an activist now, I know the purpose of being in the military is to protect and serve the constitution, that’s the same thing that we do as activists.

“We’re on a different kind of battlefield, a different kind of front line!”

“What we show is we are willing to die for our country, at the minimum we should be able to live free in that country.”

“When I go back it’s not going to be a perfect situation.”

Before the champagne starts to flow, there are more questions to be answered. It is unlikely Choi, like the thousands also discharged under DADT, will be returned to their former rank and the question of compensation has also been raised.

And just as the law has been removed, Republican presidential candidate Michelle Bachmann has announced she will try re-instating the ban if she is elected next year. Executive Director of the Service members Legal Defense Network, Aubrey Sarvis told the New York Times that this would be difficult but not impossible, effectively returning the military to the pre-DADT days when gay people were banned altogether.

So, what will Choi do from September 20?

“I’ll be happy to go back to the army,” he said.

“Even to go back through basic training, I’d be willing to do that, I don’t need to go back as my rank.”

“When we go back, we should fight for the non-discrimination policy; we should fight for marriage equality and the right to have our families supported, just like straight families; we should fight for that American flag to be given to our real partner when we die; we should fight for all of those rights and responsibilities.”

Benn Dorrington

Love OUTinPerth Campaign

Help support the publication of OUTinPerth by contributing to our

GoFundMe campaign.