Before there were workplace Pride groups in large companies, and the annual parade through Northbridge attracted thousands of spectators, life for LGBTI people was very different.

Back in the 1970’s homosexuality was still a long way off from being decriminalised, there was no gay press, and mainstream media certainly had nothing positive to say about queer people.

At the start of 1970’s, a little more than a year after New York’s Stonewall riots for gay liberation, Australia’s push for LGBTI rights began. The Campaign for Moral Persecution (C.A.M.P) for formed in Sydney in September 1970, and it quickly had branches across the nation.

They declared the overall aim of CAMP was to “bring about a situation where homosexuals can enjoy good jobs and security in those jobs, equal treatment under the law, and the right to serve our country without fear of exposure and contempt.”

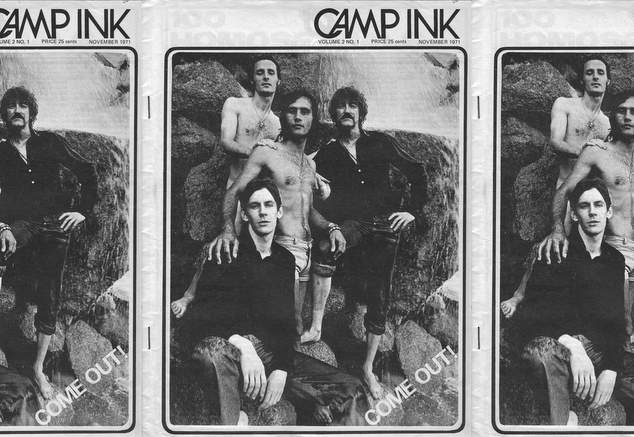

The organisation soon began publishing it’s own member’s magazine, CAMP INK which in a time before the internet, when interstate phone calls were still prohibitively expensive, connected gay and lesbian people across the country, creating shared information and solidarity.

OUTinPerth’s archives have a physical copy of an issue of CAMP INK from November 1971. The first issue of the magazine a year earlier saw 500 copies printed, within a year they were printing 5,000 across the country. The issue we have a copy of is the Queensland edition.

The November 1971 edition, which cost 25 cents, features a report focussing on a survey of 100 homosexual in Queensland who shared their experiences about sexuality, there were updates on the local gay scene, there’s a comic about a superhero – he’s called Super Phalla, and he’s a gay liberator from a distant planet.

Letter to the editor discuss federal Attorney General Tom Hughes, complaining that while the AG has spoken about decriminalising homosexuality, there didn’t actually seem to be a lot of action from his party on the issue.

There’s also a letter encouraging people to use their own names when writing submissions to the magazine rather than uses pseudonyms or abbreviations.

“If even one member of this minority group cannot his or her legal name to the other members without the fear of some form of exposure, or recrimination, then what hope do we have of achieving our aims.” Richard Roberts of Brisbane wrote. “The straight world will continue to treat us like a smutty joke if we continue to cower in the chiaroscuro of the beats and the bars, reaching out of our loneliness for love.”

There’s also an update from Western Australia, where 125 people had joined the organisation. he group had held some larger public meetings before breaking off into small groups to tackle different issues, usually at wine and cheese evenings.

They note that WA has just had a new Labor government under John Tonkin, and discussing the decriminalisation of homosexuality was back to square one with the appointment of a new Attorney General.

The local group is described as a few people who were doing a lot of the heavier lifting while others were quite lethargic. The author of the report also notes that not enough women are involved in the campaign.

Local man Steve Rand first got involved with the organisation in 1974. He remembers spending his Thursday nights at their meetings in Hay Street where there was a party and a regular women’s group.

To reconnect activists who were involved in C.A.M.P. Steve’s sent up a Facebook group for people to join and share their memories.

Read issues of CAMP INK at the Pride History Group and if you were part of the organisation back in the day, head to Facebook to join the reunion group.

Graeme Watson