In 1725 Leendert Hasenbosch was marooned on an island

Leendert Hasenbosch was an employee of the Dutch East India Company who was marooned on an uninhabited island in the South Atlantic Ocean after his shipmates found him guilty of the crime of sodomy.

Hasenbosch was born in Holland, probably around 1695. When he was a teenage his father, who was a widower, moved to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies with his daughters leaving his teenage son in Holland. What was known as Batavia is now part of Indonesia.

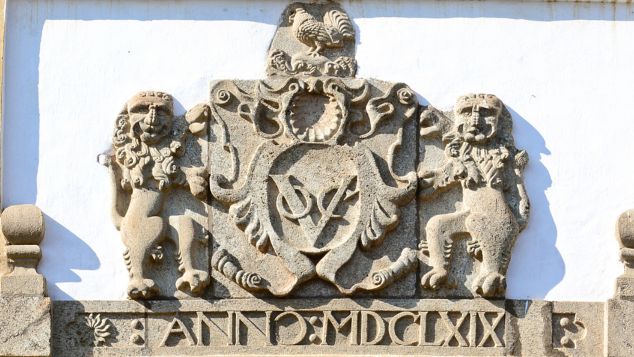

In 1714, he joined the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), known in English as the Dutch East India Company. Hasenbosch served as a soldier and was travelled to Batavia where he served for a year. Later he spent time working for the company in India. In 1720, he returned to Batavia and was promoted to the rank of corporal.

On 17th April 1725 he was convicted of sodomy following his ship making a stop in Cape Town, South Africa. As punishment he was marooned on Ascencion Island on this day in 1725. The volcanic island is 1,600 kilometres from Africa, and 2,300 kilometres from South America.

He was left with a month’s worth of water, some seeds, prayer books, writing materials and some clothes and a tent. It is presumed that he died about six months after he was left on the island.

In January of the following year, British sailors discovered his tent and his diary. The original diary was lost long ago but copies of the translation that was published in Britain give us some idea of what happened after he was abandoned on the island.

Unable to find a constant supply of water Hasenbosch reported took to drinking his own urine, and also tried drinking the blood of turtles and sea birds. It is believed that he eventually died of thirst, but his body was never found.

Over the centuries various versions of his diary were published, often attributed to an unknown sailor. Their accuracy becoming less reliable with each passing iteration.

In 2002 Dutch historian Michiel Koolbergen confirmed the identity of the marooned man was Leendert Hasenbosch. His book A Dutch Castaway on Ascension Island in 1725 was published posthumously in 2006.

Two years after Hasenbosch was marooned the crew of the Dutch East India Company’s ship The Zeewijk became shipwrecked on the Abrolhos Islands in June 1727. The crew survived on the islands as there was fresh water and plentiful food sources, long boats from the wreckage also were recovered.

In December 1727, two other young men who were part of the ship’s crew were found guilty of sodomy and transported to separate islands where they were left to die.

The picture that changed the face of AIDS

David Kirby was gay rights activist in the USA, he died on this day in 1990 aged 33 years.

Kirby had lived in Los Angeles, and was estranged from his family, but after he learned he had contacted HIV he got back in touch with his family. In 1990 he asked if he could come home to Columbus in Ohio so he could be surrounded by those he loved when he died. His family welcomed him back.

At a time before treatments had been developed those contracting HIV faced a grim future. Kirby spent his final weeks at Paster Noster House, an AIDS hospice.

Here he met Therese Frare, a journalism student who was volunteering at the facility but had also begun taking black and white photos of the people she was surrounded by.

Kirby invited Frare took take photos of his family saying their final goodbyes to him on the day he died. The image of Kirby emaciated and being embraced by his father, sister and niece look on was later published in LIFE magazine.

Frare’s image won the 2nd prize in the 1991 World Press Photo General News contest, which saw it republished around the globe.

The family later allowed the image to be colourised and used in an HIV awareness campaign by fashion brand United Colors of Benneton. They hoped the powerful image of their moment of grief would bring more attention to the reality of the AIDS epidemic.

The campaign was criticised by the Catholic Church who believed the image was an inappropriate allusion to the artistic imagery of the Virgin Mary cradling Jesus after the crucifixion. It had not been staged though; it was just a moment in time powerfully captured.

The picture is credited with having a significant impact on changing attitudes about HIV and showing the humanity of those affected by the disease.