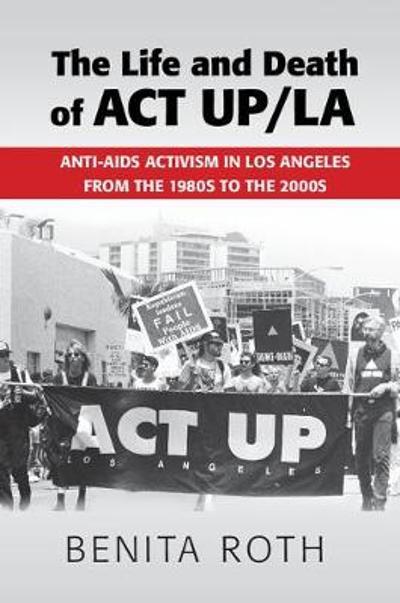

The Life and Death of ACT UP/LA: Anti-AIDS Activism in Los Angeles From the 1980s to the 2000s

The Life and Death of ACT UP/LA: Anti-AIDS Activism in Los Angeles From the 1980s to the 2000s

Benita Roth

Cambridge University Press

★★★★

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) formed in New York in 1987 as a coalition of direct-action activism in order to put pressure on the U.S. Government, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Pharmaceutical Companies to address the AIDS epidemic in a meaningful and equitable way.

ACT UP’s activism variously involved challenging drug research/approval methods, discriminatory legislation and practices against people living with HIV/AIDS, while also promoting safe sex/harm reduction initiatives, education about HIV/AIDS, and demanding universal healthcare access.

The methods utilised by ACT UP members (‘members’ is a strange term, since official membership did not really exist in the coalitions) included a whole repertoire of civil disobedience actions, such as ‘kiss ins’, ‘die ins’, ‘sit ins’, and a variety of loud and very queer demonstrations and protests.

The phenomena of ‘ACT UP’ spread across the globe as a loose model to protest various aspects of inaction over HIV/AIDS. Many ACT UPs demobilised by the late ‘90’s, and the success of protease inhibitors and combination therapy in circa 1996, along with factionalism in ACT UP chapters, disagreements over intersectionalities of gender and race, and the professionalisation of activists into HIV/AIDS service provision/research are cited as common reasons for the demobilising of respective ACT UP chapters.

The Life and Death of ACT UP/LA takes this story and specifically explores the ACT UP chapter in Los Angeles (or ACT UP/LA). Utilising archival material and interviews, Benita Roth weaves a complex trajectory of the various successes, failures, and challenges of ACT UP/LA.

Roth argues that the demise of ACT UP/LA had less to do with ‘success’ (ACT UP/LA had signs of fizzling out around 1993-94), and more to do with the deaths of key charismatic leaders (there were not any official ‘leaders’ in ACT UP movements, but in any unstructured coalition, certain people take on leadership roles), and a commitment to anti-establishment grassroots activism that saw ACT UP/LA refusing any funding attached to becoming ‘too organised’, which may or may not have saved ACT UP/LA by the mid-’90’s.

It is difficult to comprehend the complex dynamics of AIDS activism in the late ’80’s and early ’90’s – activists were simultaneously protesting while also responding to localised pressures and issues, dealing with homophobia, sexism, and HIV stigma, and grieving over the deaths of loved ones and peers. Roth effectively decentralises the ACT UP/NY story (which is often celebrated as the prototype of ACT UP chapters) and focuses on the local histories and perspectives of ACT UP/LA.

Readers interested in activist and social movements will enjoy exploring ACT UP/LA’s tensions over informal/grassroots vs. formal/professional organising, politics over insiders/outsiders of movements and institutions, challenges over maintaining a ‘leaderless’ movement, disruptions and provocations over intersectionalities within communities impacted by AIDS, and broader questions about how movements are remembered, recorded, and the efficacy of their actions.

Roth’s text also contributes to understanding the important history of women and feminist thinking within the AIDS epidemic, both in terms of the women’s caucus in ACT UP/LA, as well as exploring how women’s issues around the AIDS epidemic were talked about in the general meetings and through protests. Researchers interested in qualitative methodologies and queer archival research will also find valuable insights in the appendix chapter.

Roth’s text is less accessible for readers who are not very familiar with HIV/AIDS politics/history or ACT UP movements, and the text is definitely more scholarly and less of a ‘general read’. Furthermore, if the text is strong in its critical treatment of thematic issues around activism, I felt that it was weaker as an overall ‘narrative’.

In its focus on the locality of Los Angeles I found it difficult to match up the activism to the broader timeline of HIV/AIDS activism in the U.S., and a focus on situating the ‘glocal’ would have strengthened the text’s existence within the discourse of broader HIV/AIDS history.

Taking those limitations into account, Roth has contributed an important piece to better understanding these important topics, and at a time when there continues to be a need for nuanced political movements, it serves as a great case study to critically think about best practice in activism.

As a final comment, I found it strange that Roth uses the term ‘Anti-AIDS Activism’, which denotes the efforts by activists concerned with stopping the transmission of HIV and access to (often experimental) treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS.

The use of ‘Anti-AIDS’ seems a bit sloppy, because the opposite, ‘AIDS Activism’, does not refer to the promotion of HIV transmission and the development of HIV into AIDS. It’s a bizarre phrase to use, and given that there’s a precedence of using ‘AIDS activism’ in the existing corpus of HIV/AIDS research, ‘anti-AIDS Activism’ at first glance would imply counter-demonstrations of AIDS activists.

While it would be wrong to judge the overall worth of this text on the basis of this semantic issue, it certainly made me hesitant to pick up the book.

Anthony K J Smith

Support OUTinPerth

Thanks for reading OUTinPerth. We can only create LGBTIQA+ focused media with your help.

If you can help support our work, please consider assisting us through a one-off contribution to our GoFundMe campaign, or a regular contribution through our Patreon appeal.